Nsibidi begins like a whisper an old language without sound, born before letters, before borders, before the idea of modern Nigeria itself. To encounter Nsibidi is to enter a world where meaning is drawn, not spoken, and where symbols carry the weight of secrets, ceremonies, and centuries of human experience.

For many young Africans today, it feels almost mythical mysterious signs carved into calabashes, walls, fabric, and memories yet this ancient system is one of the continent’s earliest forms of writing, quietly alive beneath the noise of modernity.

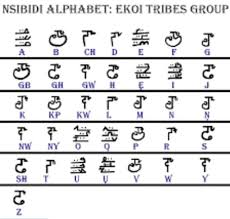

Long before the arrival of colonial administrators or missionaries, Nsibidi thrived among the Ejagham people of the Cross River region, spreading over generations to the Efik, Ibibio, and Igbo communities. It was more than communication; it was a cultural institution. Anthropologists date its origins back hundreds of years, possibly more than a millennium.

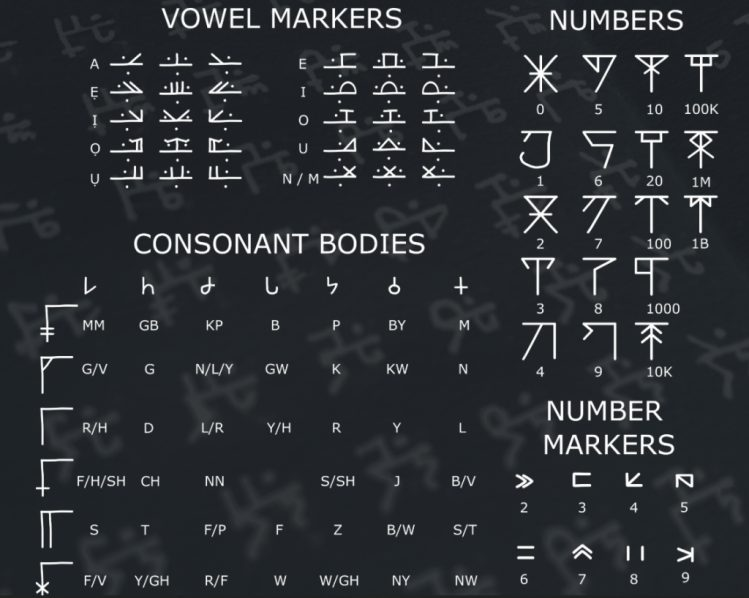

In its earliest forms, Nsibidi served as both a language and a visual philosophy—one that blended beauty, meaning, and ritual in ways Western writing systems never quite matched.

In markets and meeting squares, Nsibidi once guided decisions, settled disputes, and preserved stories. Symbols represented ideas like love, friendship, war, unity, marriage, and justice. They were drawn on pottery, etched into walls, woven into cloth, and even danced into the air during masquerade performances.

Each symbol had a life of its own. The more complex symbols were reserved for initiation into the Ekpe or Ngbe secret societies, which guarded the most sacred knowledge and transmitted it across generations through ceremony and discipline.

Members of the Ekpe society used Nsibidi as a tool of governance, justice, and social order. Court judgments were recorded in symbols. Agreements between families, lovers, and communities were encoded in intricate drawings.

At a time when many African societies relied on oral tradition, Nsibidi provided a visual archive a system that could store memory, mark boundaries, and keep secrets all at once. It was writing, yes, but also art, law, spirituality, and identity bound together.

Even in its simplicity, Nsibidi carried deep nuance. A symbol could shift its meaning depending on context, the gender of the interpreter, or the ceremony in which it appeared.

Some marks were public, others private, and some restricted to those whose initiation granted them the privilege of interpretation. This layered structure created a cultural ecosystem in which knowledge was treated with reverence, not simply recorded for anyone to read.

But with the rise of colonialism came disruption. Missionaries condemned Nsibidi as pagan, secretive, or dangerous. Western education replaced local systems of knowledge, and many custodians of Nsibidi went underground. Some symbols were lost entirely; others survived only because elders silently protected them. A rich intellectual and artistic system, one of Africa’s earliest writing traditions, was pushed to the margins of its own homeland.

Yet Nsibidi refused to die. Like many indigenous traditions, it simply lay dormant waiting. And in the early 21st century, something unexpected began to happen. Young Africans, artists, historians, and scholars started looking back, searching for cultural anchors in a rapidly globalising world. They found Nsibidi again. They found its stories, its beauty, its depth. And they began to bring it back to life.

Today, Nsibidi is undergoing a vibrant rebirth. Fashion designers use its symbols on jackets, beads, and streetwear collections. Visual artists reinterpret ancient signs in murals and digital art.

Afrofuturist storytellers incorporate Nsibidi into comics, film worlds, and speculative narratives. Even musicians and tattoo artists draw inspiration from the ancient script, giving it a modern stage without stripping it of its rooted meaning.

In universities—especially in southeastern Nigeria and across the diaspora anthropologists and historians are re-documenting symbols, tracing their cultural significance, and cataloguing surviving knowledge from elders and secret society members.

Nollywood films now include Nsibidi-inspired scenes, and social media creators use the symbols as gateways to African pride and identity reclamation. What was once hidden is stepping back into the public imagination, one symbol at a time.

Still, this revival comes with tension. Some traditional custodians worry that commercialization could disrespect sacred meanings or drain Nsibidi of its spiritual depth. Many symbols were never meant to be worn casually or printed on T-shirts.

The debate continues: How do we balance cultural preservation with creative freedom? How do we honour an ancient system without diluting its soul for aesthetic trends?

At its core, Nsibidi’s modern resurgence reflects a continental yearning for reconnection. Young people across Africa are no longer satisfied with histories written solely through colonial lenses. They want their own stories, their own systems of knowledge, their own intellectual heritage. Nsibidi offers that—in all its complexity, beauty, and mystery. It stands as a reminder that African writing traditions did not begin with colonial languages but have existed for centuries.

Beyond aesthetics, Nsibidi calls Africans to reflect on identity and belonging. Each revived symbol becomes a visual affirmation: We were scholars before we were colonised. We were artists before we were documented.

We were creators of sophisticated systems long before the world was ready to acknowledge them. Nsibidi’s rebirth is not simply cultural it is psychological and political.

As researchers and cultural advocates continue to document and protect the symbols, Nsibidi becomes a bridge between the ancient and the modern. It teaches that heritage is not static; it evolves.

The symbols that once governed secret societies now help shape contemporary conversations about decolonisation, indigenous knowledge, and African futurism. Through revival, Nsibidi becomes part of a broader movement to reclaim what history tried to erase.

And so Nsibidi lives on etched on city walls, worn proudly on clothing, painted into canvases, and researched in classrooms. It is no longer confined to secrecy, yet it retains a depth that invites respect. Its modern rebirth is as powerful as its origins, reminding us that culture may bend but it rarely breaks.

In the end, the story of Nsibidi is the story of resilience. It is the endurance of memory, the persistence of beauty, and the unbroken thread connecting generations across centuries.

As Africa moves forward, Nsibidi stands as a symbol not only of the past but of the future a rebirth rooted in pride, knowledge, and the timeless human need to create meaning.