When Eric Dane first stepped onto the set of Grey’s Anatomy in 2006, no one could have known how powerfully his presence would resonate with audiences around the world. Tall, charismatic and imbued with a raw vulnerability masked by a playful swagger, Dane’s portrayal of Dr. Mark “McSteamy” Sloan captured hearts and headlines. Over the years, he moved effortlessly between genres – from the post‑apocalyptic drama The Last Ship to the nuanced world of Euphoria, but it was his capacity to disappear into a role, while remaining keenly aware of the humanity behind it, that defined his career.

In April 2025, Dane shared a deeply personal chapter of his life with the world: he had been diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a progressive neurological disease also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. The news sent ripples through Hollywood and beyond, not as a footnote, but as a profound reminder that even those who seem larger than life face battles unseen by the public eye.

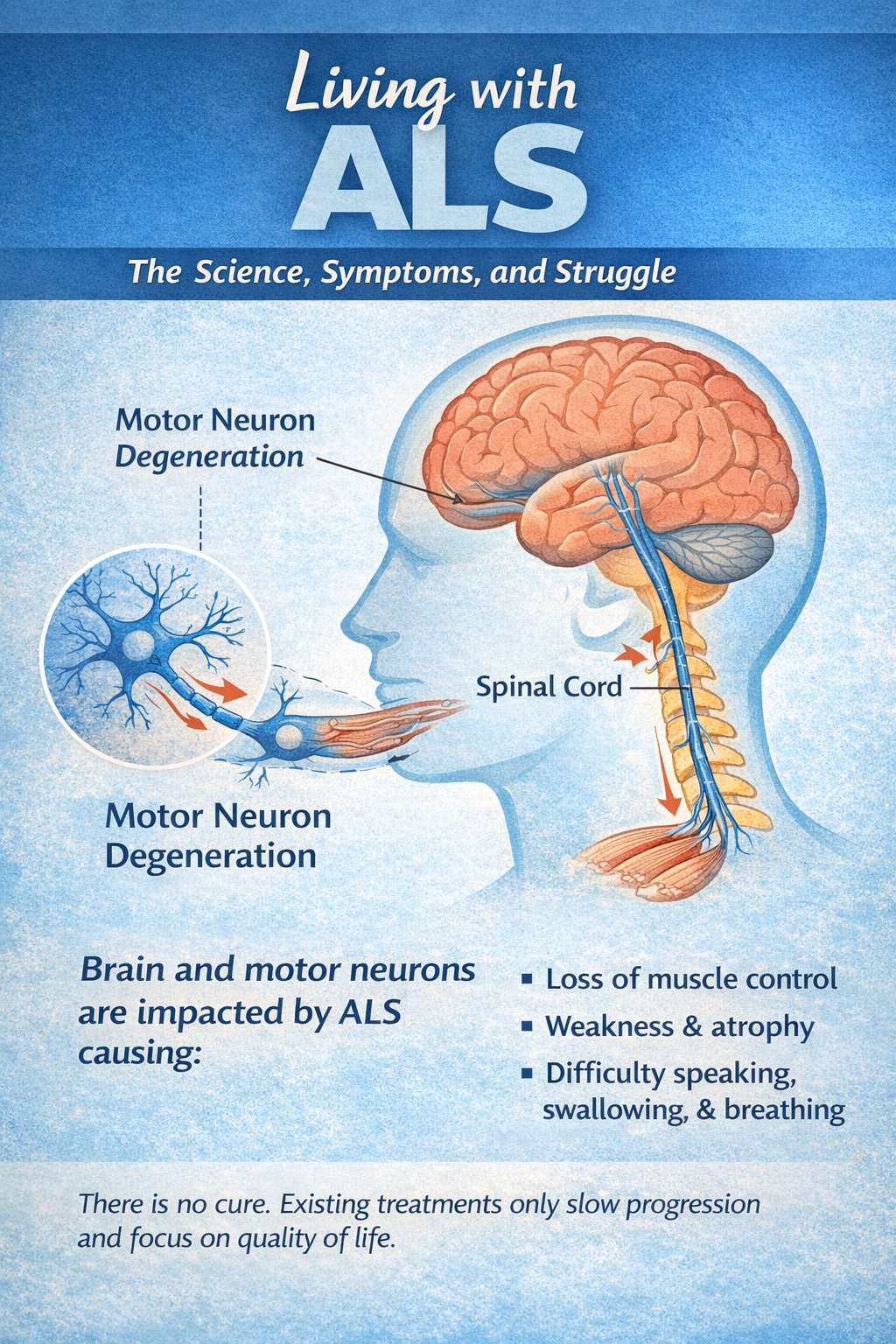

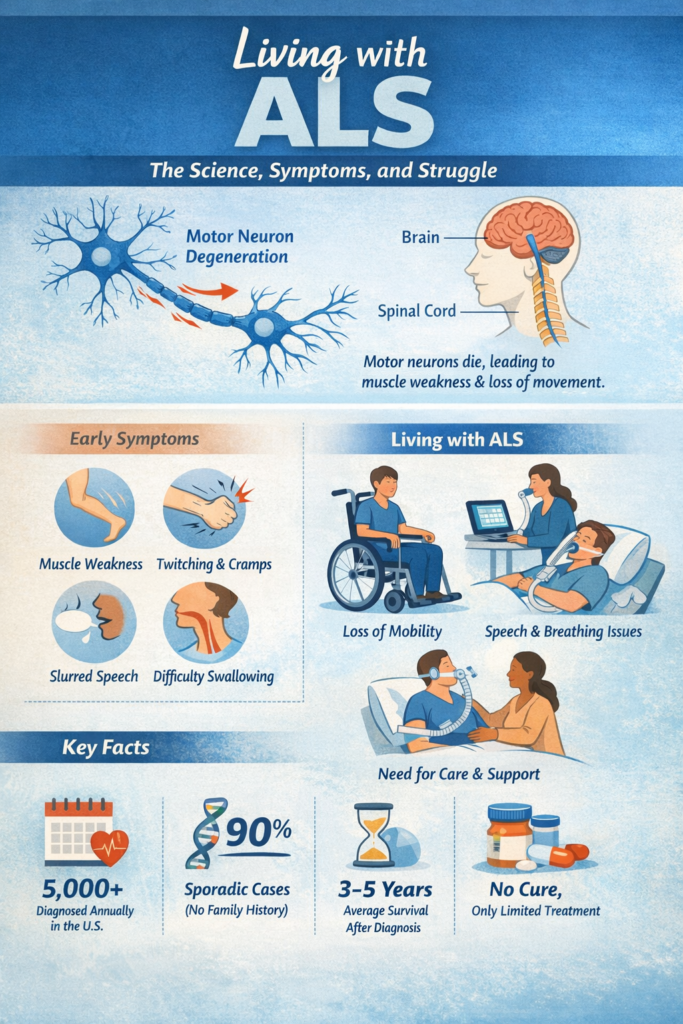

ALS is a progressive neurodegenerative disease a condition of the nervous system that slowly destroys the very cells the body needs to function. In people with ALS, the motor neurons, the nerve cells that run from the brain and spinal cord to the muscles begin to deteriorate. Without these pathways, the brain’s signals no longer reach the muscles, and muscles gradually weaken, shrink, and lose the ability to perform even the simplest voluntary movement, like lifting an arm or speaking a sentence.

Most people living with ALS eventually lose the ability to walk, use their hands, talk clearly, swallow food, or breathe independently. The disease typically progresses over a period of three to five years after diagnosis, though there can be variability; some people experience slower progression, others faster. There is currently no cure, and existing treatments aim only to slow decline or support comfort and quality of life.

ALS gets its name from the words that describe what happens inside the spinal cord – amyotrophic referring to the lack of muscle nourishment, and sclerosis to the scarring that develops as motor neurons die. The disease does not affect mental functions or the senses, meaning that people with ALS often remain cognitively aware even as their bodies fail.

Scientists do not yet fully understand why ALS occurs. In roughly 90% of cases, there is no known family history or genetic cause, a classification known as sporadic ALS. Only about 5 – 10% of cases are inherited, or familial, often involving known genetic mutations, though researchers continue searching for others. Environmental factors, lifestyle, and unknown triggers are subjects of ongoing study, but no single cause has been identified for most people who develop the disease.

When ALS begins, symptoms can be subtle. A person might notice weakness in a hand, a foot that drags while walking, or muscles that twitch and cramp. These signs are easy to dismiss at first, but they reflect the early loss of motor neurons. As the condition advances, coordination worsens, speech may become slurred, and swallowing grows difficult. Respiratory muscles weaken as the disease reaches its final stages, making breathing the most critical concern.

To grasp how rare yet devastating ALS is, consider the numbers. In countries with large health systems, roughly two to three people per 100,000 are diagnosed each year, and as many as 1 in 300 people may face the disease over a lifetime. In the United States alone, data suggest tens of thousands live with ALS at any given time, and cases are expected to grow modestly over the next decade. The condition affects people of all races and ethnicities, and while it appears slightly more often in men than women, it remains rare overall.

Because ALS progresses differently in every person, the lived experience varies. Some patients may lose the ability to walk early but retain strong hands for communication. Others might first struggle with speech or swallowing. Supportive care from physical and occupational therapy to ventilator support and communication devices aims to preserve independence as long as possible. Medications like riluzole and others approved in some countries may modestly slow progression, but they do not cure the disease.

For Dane, the early signs began months before diagnosis with symptoms in his right hand that he initially attributed to fatigue or overuse. After clinics and specialists ruled out other causes, neurologists confirmed ALS an announcement he made public not to seek sympathy but to shine a light on a condition that many people only vaguely know by name. “Some of you may know me from TV shows,” he said at a news conference in Washington as he advocated for improved health insurance policies and increased research funding, “but I am here today to speak briefly as a patient battling ALS.”

His final public appearances captured the raw effect of the disease: nerve damage that made simple movements difficult, and yet a resolve to use his platform to raise awareness. In December 2025, on a virtual panel for an ALS advocacy organization, he called the condition “so horrible,” but he also spoke candidly about his refusal to let it erase his sense of purpose.

Because ALS erodes physical function but not mental acuity, emotional and psychological coping are crucial. Patients often describe the growing gap between their awareness and their bodies’ shrinking capabilities as one of the hardest parts of the journey. Caregivers and health professionals emphasize communication, comfort, and dignity for those living with the disease.

Eric Dane’s death brought widespread tributes not only for his decades of work on screen but also for the visibility he gave to ALS. Friends and fans shared stories of his warmth and humour even in decline, and his family’s announcement asked for privacy while acknowledging the outpouring of support for his daughters.

The world continues to search for better treatments and ultimately a cure. Research efforts focus on understanding why motor neurons die, identifying genetic and environmental risk factors, and developing therapies that can halt or reverse the disease’s progression. In the meantime, raising awareness as Dane did in his final year remains vital for funding, early diagnosis and the development of new medical approaches.

ALS is a rare, relentless disease that touches few directly but resonates widely when someone like Dane shares the journey publicly. In educating about the science, numbers, and human experience of ALS, stories of those affected become more than headlines; they become bridges to understanding, compassion, and the urgency of medical progress.