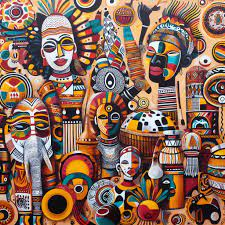

People move for many reasons: work, safety, school, love. In Africa today, migration is no longer a side story – it is one of the main forces quietly remaking how people see themselves and each other. When millions of people move inside the continent or travel to Europe, the Americas, the Gulf or within African cities, they carry more than luggage: they carry songs, food, fashions, religious practices and family rules.

Over time, those things mix with local ways and create new cultural blends that feel African but are also different from what existed before. This shift is big enough that experts studying movement across Africa say migration is central to how societies are changing on the continent.

One of the clearest markers of cultural change is money that moves with people. Remittances the money migrants send home — do more than help families pay bills. They fund celebrations, weddings, and small cultural projects; they pay for music studios, festivals, or building a church or mosque.

That money encourages new cultural tastes and helps migrants keep ties with their home towns while also adopting tastes from where they live now. Development institutions have long noted that diaspora money and skills are a major channel linking culture, identity and local change back home.

Diasporas also reshape what it means to be African in foreign countries. In cities like New York, London, Lagos, or Johannesburg, second-generation Africans grow up with mixed influences: the home language, the school language, social media, and neighbourhood traditions.

Studies show that African immigrant communities are diverse and growing, and their children often create hybrid identities they call themselves Nigerian-American, Kenyan-British, or simply global in a way that blends home and host cultures. These identities aren’t a loss of culture but a new form: cultural practices adapt, and new norms and arts emerge from the blending.

Language and faith travel with migrants and change as they land in new places. African languages mix with English, French, Arabic and local tongues to form slang, new music lyrics and new forms of worship. That mixing shows up in churches and mosques where migrant communities adapt services to include music, dance, or speech patterns from home.

UNESCO and other cultural bodies work to protect the rights of migrants to keep their cultural life and to help host countries include migrants in cultural programmes – because belonging to cultural life helps reduce tensions and build social bridges.

Cities inside Africa have become crucibles of identity change. Rapid urban migration people moving from rural areas to fast-growing cities brings different ethnic groups into daily contact. In markets, nightclubs, streets and transport hubs, tastes cross-pollinate: fashion trends travel faster, musicians collaborate across languages, and food stalls sell hybrid dishes.

The IOM and regional reports point out that internal mobility in Africa is massive and that urban life speeds cultural blending; as people meet daily, practices merge in practical, sometimes surprising ways.

Music, film and fashion are the loudest visible signs of migration’s cultural effect. Afrobeats, for example, is a product of local rhythms meeting global sounds and diasporic influences; the genre’s global rise is both a cultural export and a mirror for new identities.

Nollywood films now speak to diasporic audiences and sometimes shoot abroad; fashion designers borrow traditional textiles and add international cuts and styles that appeal to young Africans everywhere. These art forms become mobile identity markers – when someone wears that hat, plays that song, or watches that film, they signal a modern, connected African identity that travels.

Return migration and circular movement when people go abroad, gain skills, and then come back also reshapes identities at home. Returnees bring new business ideas, new musical tastes, new religious practices, and sometimes new social norms about gender or work. That can create healthy innovation but also friction when returnees expect quick change and local communities move more slowly.

Policymakers and local leaders often face the task of harnessing returning skills while respecting local customs; the net effect is usually an evolving, not erased, identity. Reports on diaspora engagement and development stress both the opportunities and the social tensions linked to return migration.

Migrants also change family life and social rules. Transnational families where parents work in one country and children stay in another — negotiate identity across borders. Children may grow up with grandparents in the home country and parents abroad, and this shapes loyalty, language use, marriage choices and even food preferences.

Social media and cheap communication keep families connected, so cultural transmission is faster but more complex: traditions are preserved in new formats (video calls to teach a recipe, online music playlists for festivals) and family identities become partly digital and partly local. Studies of migration and family life underline how mobility rewrites family roles and cultural expectations.

Host societies also change because of migration. When communities welcome migrants into schools, markets and workplaces, new cultural practices become part of everyday life for everyone. That can mean new foods on offer, different festival celebrations in public space, or more multilingual signage.

At the same time, friction can appear when economic stress, discrimination, or poor integration policies make migrants feel excluded. International bodies recommend cultural inclusion programmes shared festivals, cultural centers, public arts funding as ways to turn cultural mixing into social cohesion. UNESCO and other agencies emphasize cultural participation for refugees and migrants as a way to build trust and reduce conflict.

Looking ahead, migration will keep shaping African identities in ways that are both hopeful and challenging. On the hopeful side: stronger transnational ties can generate creativity, remittances can fund cultural projects, and younger generations can invent identities that feel whole even when mixed.

On the challenging side: unequal migration experiences, xenophobia in host places, and the loss of some local skills or languages are real risks. The policy answer is not to stop movement which is impossible and often harmful but to invest in programs that protect cultural rights, support inclusive cities, and link diaspora skills to local development. In that balance, migration becomes less a threat and more a source of renewal for African cultural life.